Saving Banks - And The Taxpayer

By Colin Twiggs

March 2, 2009 9:00 p.m. ET (1:00 p.m. AET)

These extracts from my trading diary are for educational purposes and should not be interpreted as investment or trading advice. Full terms and conditions can be found at Terms of Use.

Nationalization By Instalment

Insurer AIG posted a record $61 billion loss for the fourth quarter. Treasury is to provide up to $30 billion of preferred share funding, increasing their equity interest to just below 80 percent (WSJ). Government also recently converted $25 billion of its preferred stock in Citigroup into 36 percent of the common stock. Taxpayers may feel aggrieved as common stock was purchased at roughly three times the current market price of $1.50. Equity stakes in the financial sector are expected to grow as housing prices fall and bank losses continue to rise.

Former banker James Wood points out that TARP assistance may be a double-edged sword, with assisted banks classed as high risk and unable to raise funds in the market place. This has led some banks to consider returning TARP funds in order to avoid the stigma — and also avoid government interference on issues such as employee compensation.

Cost Of Saving The Banks

President Obama's 2010 budget plan provides for another $750 billion in assistance to the financial services industry — in addition to the existing $700 billion TARP. Apart from becoming a bottomless pit, with the gradual collapse of some major institutions absorbing more and more taxpayer funds, treasury assistance may further tarnish the sector's image — making it even more difficult to restore stability in the market place. Susan Woodward and Robert Hall highlight an elegant alternative, credited to Jeremy Bulow of Stanford GSB, that would restore stability to the financial sector without costing the taxpayer a cent.

An Elegant Solution

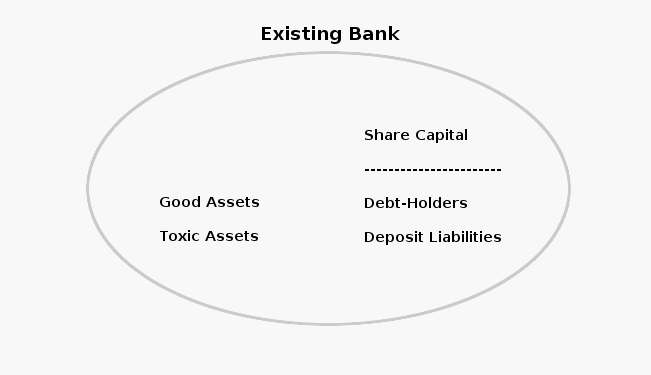

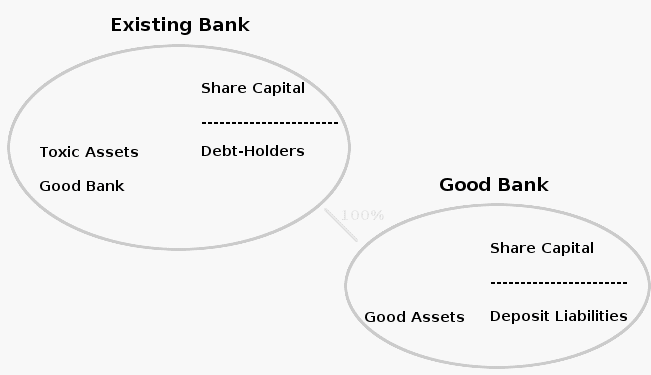

Bulow's idea is simple: take all the sound assets owned by a troubled bank and all its deposit liabilities and inject them into a new, good bank funded with adequate share capital. The value of the new bank is likely to far exceed the value of the existing bank and, because it is 100 percent owned by the existing "bad" bank, may enhance its value too. All troubled assets are left in the holding company. As are existing shareholders and debt-holders (other than depositors), including longer term bond-holders and holders of short-term commercial paper.

The new bank will have a sound balance sheet, untainted by the stigma of troubled assets that currently beset the "bad" bank. Adequately capitalized, the good bank would be valued at a premium to its assets, forming a sizable asset on balance sheet of the "bad" holding bank. And none of shareholders and debt-holders rights to the residual value of good or bad assets would be wiped out — as in the case of nationalization.

If, at a later stage, the residual value of the assets is found to exceed the holding company's debts, shareholders will be able to salvage some of their equity. But if debts exceed asset values, shareholders will lose their equity. And debt-holders will be required to take a haircut, to the extent of any shortfall.

Outcome

The "bad" bank would cease to operate as a bank and become a holding company. Continuing with existing shareholders and debt-holders, other than depositors, its assets would consist of 100 percent of the stock in the good bank and all troubled assets from its previous operations. Failure of the holding company would have minimal impact on the operations of the good bank — and on the banking sector as a whole. Stock in the good bank could simply be sold off, along with the other assets of the holding company, to the highest bidder.

When people begin anticipating inflation, it doesn't do you any good anymore,

because any benefit of inflation comes from the fact that you do better than you thought you were going to do.

~

Paul Volcker

Author: Colin Twiggs is a former investment banker with almost 40 years of experience in financial markets. He co-founded Incredible Charts and writes the popular Trading Diary and Patient Investor newsletters.

Using a top-down approach, Colin identifies key macro trends in the global economy before evaluating selected opportunities using a combination of fundamental and technical analysis.

Focusing on interest rates and financial market liquidity as primary drivers of the economic cycle, he warned of the 2008/2009 and 2020 bear markets well ahead of actual events.

He founded PVT Capital (AFSL No. 546090) in May 2023, which offers investment strategy and advice to wholesale clients.